This question has come to shape many of my conversations over the years as a Palestinian in exile. For as far as I can remember, the question has changed the course of dialogue with any person I have met.

I remember sometime back in elementary school, possibly first or second grade, I was asked that question by one of my classmates. I can’t remember the exact context of the conversation; maybe it was after a summer trip to Gaza (my hometown). When I told him about the trip, he asked: “So you’re from Israel?” Given that we were so young and innocent back then, he didn’t understand the difference and started yelling, “So you’re an Israeli? Guys, Sami is an Israeli.” It was break time and we were the last two students running down the stairs, so I took the time to explain to him the difference between being a Palestinian and being an Israeli.

Growing up in Cairo, the Egyptian capital, my family did what many other Palestinian families in exile did: they made sure that we understood that distinction. My brother, my sisters, and I were raised in a house that exuded Palestinian culture. Even though we were born and raised in Egypt, my parents spoke to us at home in Palestinian Arabic, specifically in a slightly refined Gazan dialect. We were also fortunate that my aunt lived one floor below us and my uncle lived two floors above us. Their presence made us feel that the building was safe, since we were all caring for one another and speaking the same dialect – similar to what goes on with families in Gaza, living so close to each other.

Having said that, we still brought the Egyptian dialect into our conversations at home from time to time, especially when it came to joking or laughing. After all, we were living in Egypt, and Egyptians are known for their great sense of humor, some of which our family acquired. It was even funnier when we switched to using the Palestinian dialect in front of our school friends. Their suspicious looks seemed to be asking, “Who is this person, and what has happened to my friend?” For them, the fact that we were able to switch between dialects was a phenomenon worth studying. Similar to the dialect diversity in the United Kingdom, for example, it seemed to them as though we were multilingual.

♦ “There are more than five million Palestinian refugees registered with the United Nations, making up the largest group of refugees in the world. The Palestinian refugee advocacy group BADIL estimates that there are an additional 2.7 million unregistered Palestinian refugees, making up 66 percent of the Palestinian population worldwide.” (https://electronicintifada.net/content/photos-generations-palestinian-exile/13506)

In our Mohandeseen apartment, we had an arabesque living room with about half a dozen colorful Palestinian embroidered cushions decorating each couch. Each cushion represented a different geographical location in Palestine, a piece of information I learned only later on in my adulthood. A few prints by the famous Palestinian artist, Ismail Shammout, hung along the living-room walls, and an embroidered map of Palestine was also proudly featured.

Our kitchen was filled with Palestinian spices such as dukkah and za’atar, small metal containers filled with Palestinian olive oil, and various sizes of glass jars packed with Palestinian olives. These ingredients were, and still are, an integral part of our breakfasts and dinners. Arabic pita bread dipped into oil and then the dukkah and za’atar followed by a few green olives and some hummus or labneh, is a meal that I still can’t get enough of.

Our dining room never failed to accommodate huge numbers of our immediate family members and friends, both Egyptian and Palestinian, and delighted them with delicious Palestinian dishes; maqlouba, fatteh with zaghaleel, ruz qidrah, you name it, we had it. Even the event-themed food, such as kaa’ik (baked date cookies covered with sugar) on Eid al Fitr or summakiyya (a Gazan dish made from sumac spice), was prepared by my mother, God bless her, who learned at an early age the importance of cuisine in the celebration of every eid.

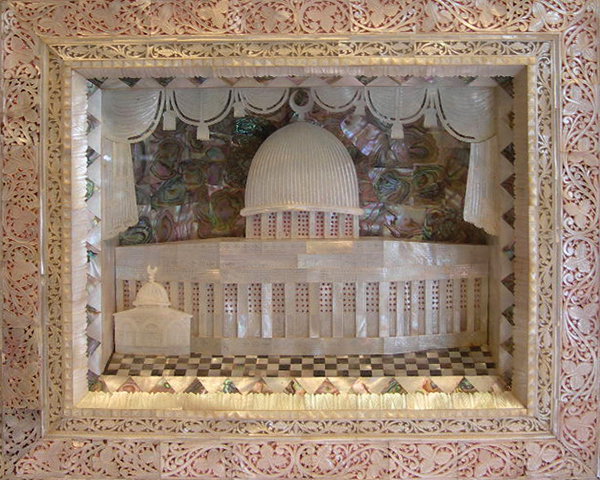

Our guest room’s central piece featured the famous Dome of the Rock that was covered in sadaf and handmade in Jerusalem. The Dome of the Rock would detach to show a storage space similar to that of a jewelry box, a red velvety fabric that covered its interior. I could swear that I used to find that same piece – in a variety of sizes – in every Palestinian house I visited.

I discovered that my mother’s wardrobe, as with that of every Palestinian woman, had more than one Palestinian dress or thobe, embroidered in different designs from various villages across Palestine, a concept similar to the living-room cushions. She also had a Palestinian embroidered shawl that went with everything. The men’s wardrobes – my dad’s, my brother’s, and mine – were not always as representative of Palestine, but we definitely had our black and white kuffiyehs in there.

During our summers, and sometimes our midterm breaks, we traveled to Gaza to keep the connection with Palestine going. It was a smart move on the part of my parents because it was like having our home in Egypt as a theoretical model, and the Gaza visits as our practical lab sessions. It was where we applied what we learned throughout the year, living in our home in Mohandeseen, that small piece of the Holy Land present in the land of the pharaohs.

During our summers, and sometimes our midterm breaks, we traveled to Gaza to keep the connection with Palestine going. It was a smart move on the part of my parents because it was like having our home in Egypt as a theoretical model, and the Gaza visits as our practical lab sessions. It was where we applied what we learned throughout the year, living in our home in Mohandeseen, that small piece of the Holy Land present in the land of the pharaohs.

I carried this way of life with me as I grew up, even though there weren’t any other Palestinians at school with me that I knew of, except my relatives. That started to change when I moved to another high school with a group of my Egyptian school friends and started to meet other Palestinians in Egypt. It was amazing how I felt a sense of identity when I met someone from my hometown. I immediately started sharing details of relatives and friends who might know them, and they did the same. During break times, even though I didn’t hang out with them much, we exchanged hellos and caught up with each other every once in a while.

♦ “Exile is more than a geographical concept. You can be an exile in your homeland, in your own house, in a room.” – Mahmoud Darwish

During my university years I discovered how many Palestinians resided in Egypt or came to Egypt to seek an education. I joined the Palestinian club and the Palestinian dabke dance group, and during almost every study year, I got to know at least one new Palestinian. There were Palestinians who resided in Egypt like me, Palestinians who resided in the Levant countries (Jordan, Lebanon, Syria), Palestinians who resided in the Gulf (Bahrain, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman, UAE), and Palestinians from Gaza and the West Bank. It was intriguing to listen to them speaking in the dialect of their country of residence or switching to the dialect of their Palestinian origin. It turned out that what happened in our household, happened with almost every other Palestinian in exile.

After graduating, I worked for a couple of years in Cairo where I met a handful of Palestinians who resided in Egypt, almost all of whom were ex-university colleagues, working at the same company. We would catch up with each other during our lunch breaks or in the early morning while sipping our coffees.

When I left my family’s place, I got a job with a company in Abu Dhabi, UAE, and moved there in 2003. I carried my Palestinian heritage with me; it created a sort of comfort zone for me. I believe that the atmosphere that one grows up in becomes a part of the self and is integrated into one’s home environment wherever that may be. Even my small one-bedroom rented apartment in Abu Dhabi had to have some Palestinian identity. The black and white kuffiyeh was there; my kitchen was filled with Palestinian spices; my new friends who visited were mostly Palestinian or Egyptian, though I also had friends from other backgrounds and cultures. I was often praised for my ability to shift between dialects and even between languages, thanks to my upbringing.

I got married while still working in the UAE, and the old embroidered cushions from home were spread on my couches in the living room. Even when the seams began to disintegrate, I didn’t give up on them. I took them to a carpenter who had an artistic touch and asked him to frame them, which he did with amazing skill. They were hung in my home in Dubai (and now in Toronto, Canada). Even though my wife is Egyptian, she is generally supportive of my Palestinian heritage. In addition to her belief in the Palestinian cause, she shows her respect for Palestinian heritage through her wardrobe. I ordered a Palestinian dress from the West Bank, bought her a Palestinian shawl, and later a shirt with Palestinian embroidery on the cuffs along with a Palestinian embroidered belt. It was as important for me to see that heritage reflected on my wife as it was to have my children grow up surrounded by Palestinian culture. My wife also spent time with my mother to learn some of our delicious Palestinian recipes. She is now a professional in preparing fattit makdoos! Although my children are getting acquainted with our spices, namely, za’atar and dukkah, the olives, and the hummus, they are still reluctant when it comes to cooked Palestinian food. I’m hoping that they will identify more with it as they develop their taste buds. I am also introducing them to the Palestinian dabke and folklore songs, and I feel they’re catching on. The only challenging part so far has been the dialect; I’m the only one who uses the Palestinian dialect at home and it is proving hard to impart to my two children. I pray that they will identify with our Palestinian dialect at some point as they grow up and speak it.

Moving to Toronto, Canada, a few years ago was a big step in my life because it was so far away from everything familiar. But we managed to transform our small apartment into a tiny piece of Palestine. The embroidered framed cushions adorn the walls, a small Palestinian sadaf map hangs near the door along with a Palestinian key holder, our kitchen is filled with Palestinian spices, and we are surrounded by some members of our extended family who immigrated to Canada over 25 years ago as well as some of my ex-university colleagues. Our closets still hold the Palestinian dress and kuffiyeh.

Understanding that I’m a soon-to-be Canadian, I still want to keep our heritage alive at home in Toronto. The beauty of multiculturalism in Canada is what mainly attracted me to this country. Everyone comes from a different region and wants to share their culture and heritage with others, keeping everyone as cultured and open-minded as can be.

Looking back on the past 15 years, I realize that I’ve always had the urge – consciously or not – to transform the places where I reside into something Palestinian, a piece of home. My parents fostered that desire. Palestine is a cause in itself, but it is also a rich and vibrant culture that needs to be shared and celebrated anywhere we go, and carried on by our children and grandchildren. Exploring and sharing our Palestinian culture elicits a joy that we should savor and cherish as long as we live.

» Sami Alshorafa is a public relations and digital communications professional and the father of twin boys. Originally Palestinian, Sami currently resides in Toronto, Canada.