As children, we were all asked the famous future-related question: What do you want to be when you grow up? The question not only burdened us with the heaviness of a major decision at a very early age, it also raised a flag that signaled how important it was for us to choose a career path, even though we had no guidance whatsoever! Little did we know how hard the choice would be, and how much it would influence every single aspect of our lives.

I had always wanted to become a teacher; but since no one guided me through the decision-making process, the dream faded and, like almost everybody else, my Tawjihi score determined my professional future. At Birzeit University I was almost dismissed for not selecting a major by the end of my second year; additional pressure! I studied psychology. I took another decision without proper guidance.

Now, 18 years after graduation, and at the age of 40, I want to become a fashion designer.

I can’t support this statement with clear-cut statistics, but I can safely argue that almost every Palestinian has experienced similar ups and downs and was forced to choose a career path or make a major professional decision without proper guidance. Many of my peers, colleagues, and friends specialized in one field and worked in another, or wanted a particular path and were forced to walk another. So why the lack of guidance?

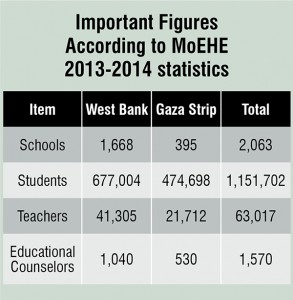

According to the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MoEHE), there are 1,151,702 students enrolled in public schools registered under the umbrella of the Ministry, which employs a total of 1,570 educational counselors for the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.i Educational, not career counselors! Pay attention.

A very basic calculation would suggest that each counselor would need to serve 733 students per school year (eight months, excluding exam periods), which is impossible, not only considering that these are educational and not career counselors, but also because these counselors are loaded with programs and tasks beyond their role descriptions and are not available in every MoEHE school.

During the past three years, I worked closely with the MoEHE as well as universities and other stakeholders in the provision of career-guidance services to Palestinian youth as part of the educational system. Despite the fact that all stakeholders realize how crucial it is to integrate career counseling in the educational system, none is visionary in terms of articulating an overall strategy to be implemented throughout the entire system. Many of the initiatives are of great quality, but coordination is absent and hence no solid impact is being witnessed.

On a school level, the MoEHE piloted a career-education curriculum for 8th, 9th, and 10th graders, and the International Youth Foundationii later built on its spirit and methodology to tailor a career-education toolkit to support 11th and 12th graders. It also introduced a partnership with Silatechiii – a Qatari organization – to provide Tamheed psychometric on-line assessment. Tamheed helps youth identify their personalities, professional preferences, and natural capacity to process information, and matches results with the appropriate career path.

When and if the implementation of self-awareness interventions at a school level is of a quality that would actually work, the questions remain about availability of specializations and quality of the educational and vocational systems in Palestine to accommodate these desires and aptitudes. What if a young man or woman wants to become a fashion designer? a dancer? a neurologist? an atomic physicist? an airplane pilot? Which of our educational and higher educational organizations are ready to offer such specializations, and more importantly, is the labor market ready to absorb such candidates?

Twelfth-grade students face their first frustration: they must be entirely dedicated to Tawjihi exam preparation. They memorize the same information I was forced to remember over twenty years ago, and they are tested on what they manage to keep in brains that were not trained to think, with information not necessarily important, information that they may or may not be interested in, using the same test I did back then!

The second frustrating youth experience occurs when one attempts to register at any given Palestinian university. Following the dramatic Tawjihi experience, students are forced to select a career path before they start their higher academic life, without benefiting from an opportunity to explore the various possible fields. Some universities prevent students from changing their minds and deny their requests to change faculty except with strict regulations that are often hard to meet. Again, students are stuck having to make life decisions without adequate guidance.

The higher educational system continues to offer traditional specializations that do not fully respond to labor-market needs; this reality restricts students’ choices and stifles creativity and innovation. Even though all universities in Palestine realize that career-guidance services are essential, they still struggle to define their interventions and do not yet possess methods to offer high-quality services. Some random attempts have taken place to coordinate with schools, but no one has taken the initiative to lead a national effort that provides a comprehensive career-guidance process that takes into account individual needs, the availability and maturity of economic sectors, and the available opportunities in an immature labor market.

For the past four years I have been working on youth employability in Palestine through the Youth Entrepreneurship Development program (YED). I carried out an assessment of career centers at nine Palestinian universities in the West Bank. The results clearly showed that, despite the interest, available services lack both diversity and quality. These nascent centers focus on alumni support with minimal services that are usually ad hoc. The assessment addressed career-center infrastructure, organizational strategy, and human resources, and analyzed the quality of career-guidance programs and services, as well as systematic monitoring, evaluation, and follow up of these services. Although the assessment findings revealed a wide variety of gap areas in these three components, additional capacity building is needed to strengthen these centers and should revolve around strategic planning, staff capacity, and provision of services.iv

The cup may seem to be half-full of belief and interest on the part of all stakeholders, but only when this belief is translated into a national strategy can we start to implement the change we want to see – a national strategy that is comprehensive and flexible, based on a clear understanding that career guidance is an ongoing service that is customized according to the uniqueness of each person and offered throughout the career decision-making and implementation process. At a school level, qualified career counselors need to be recruited, trained, and equipped with up-to-date tools and methodologies, and made available at every school. Linkages need to be created between schools and universities based on the fact that school-system outputs are university-system inputs. The labor market should regularly feed policymakers with proper and updated predictions on its needs. The educational system must respond to rapid changes and new trends by offering new fields. And every employer should offer ongoing career-planning services to its staff.

The cup may seem to be half-full of belief and interest on the part of all stakeholders, but only when this belief is translated into a national strategy can we start to implement the change we want to see – a national strategy that is comprehensive and flexible, based on a clear understanding that career guidance is an ongoing service that is customized according to the uniqueness of each person and offered throughout the career decision-making and implementation process. At a school level, qualified career counselors need to be recruited, trained, and equipped with up-to-date tools and methodologies, and made available at every school. Linkages need to be created between schools and universities based on the fact that school-system outputs are university-system inputs. The labor market should regularly feed policymakers with proper and updated predictions on its needs. The educational system must respond to rapid changes and new trends by offering new fields. And every employer should offer ongoing career-planning services to its staff.

The cycle includes many players and each needs to reclaim responsibility and coordinate with others. Leading this national effort is not the role of a counselor, nor is it the responsibility of one player rather than another. For this reason – and the fact that even today, in 2015, there is no professional support available to me as I face a radical career change – the system is not ready to claim it offers career guidance. All efforts that have been invested thus far are attempts that need to be carefully studied and learned from in order to change the system and create a decent platform for incorporating best practices in career guidance.

» Afnan Y. Mahmoud is an entrepreneurship and employability specialist at the International Youth Foundation and has been active for the past eighteen years in the field of development through a number of local and international organizations.

i http://www.mohe.gov.ps/ShowArticle.aspx?ID=335.

ii http://www.iyfnet.org/.

iii http://www.silatech.com/.

iv Palestinian University Career Guidance – “Centers’ Assessment: Findings and Recommendations,” International Youth Foundation, June 2014.